Audacious Audits: Own Your Numbers, Own Your Narrative

What if audits could become a vehicle where nonprofits proudly share program and mission stories, expressed in the language of finance? Or better yet, what if donors and the public eagerly anticipated each year’s audit as the go-to document for recounting how financial strategy integrates with mission strategy?

“Most nonprofits don’t realize that they, not their CPAs, should be writing their audits.”

Curtis Klotz, CPA

The idea that an audit could be bold or audacious rather than an expensive matter of compliance – or an obligatory jumping through hoops – might be a longshot. Especially given that CPAs talk in muted tones – a language where an “unmodified opinion” is the highest sort of praise and having “no findings” in your audit is a badge of honor. But most nonprofits don’t realize that they, not their CPAs, should be writing their audits.

At Propel Nonprofits, we chose to become an early adopter of the new FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board) standards for nonprofit financial reporting and recently completed our second audit using them. Our goal in adopting early is to use our experience to help other nonprofits prepare to adopt the standards. Here are some examples of ways (including the often overlooked use of narrative disclosures) we used the new standards to tell our mission and financial story.

Contribution and Net Asset Classification

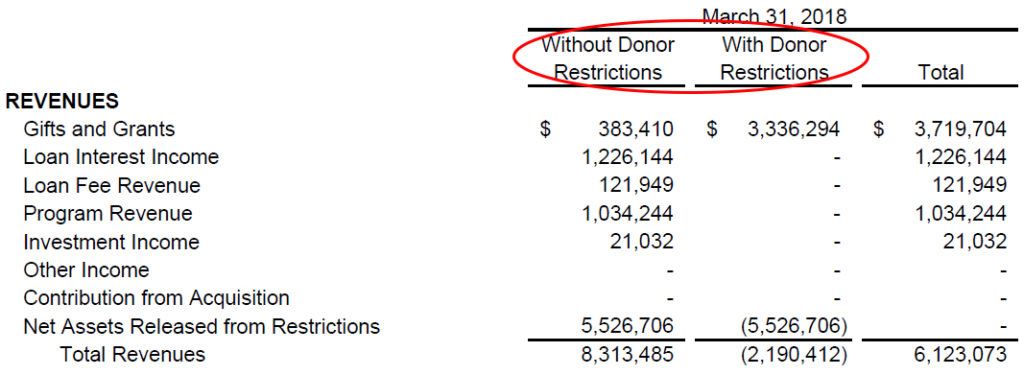

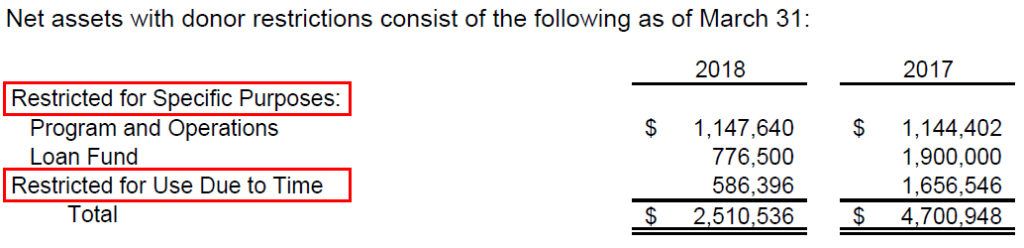

One common misconception about FASB standards is that they are a set of rules that must be rigidly followed. In reality, the standards are guidelines that set a minimum threshold for compliance, beyond which nonprofits are welcome to share more information. Your audit strategy could include meeting the basic requirements of each standard, then adding more descriptive information about your nonprofit’s way of operating. One example is the new standards that require nonprofits to track and report their contributions and net assets in two categories, “Without Donor Restriction” and “With Donor Restriction,” as shown here in the Statement of Activities. (Propel Audit, Page 4)

Adding more information in a note disclosure gives readers of the statements a deeper understanding of what kinds of contributions an organization receives and what donor restrictions might be in play. (Propel Audit, Page 22)

Functional Expenses by Nature

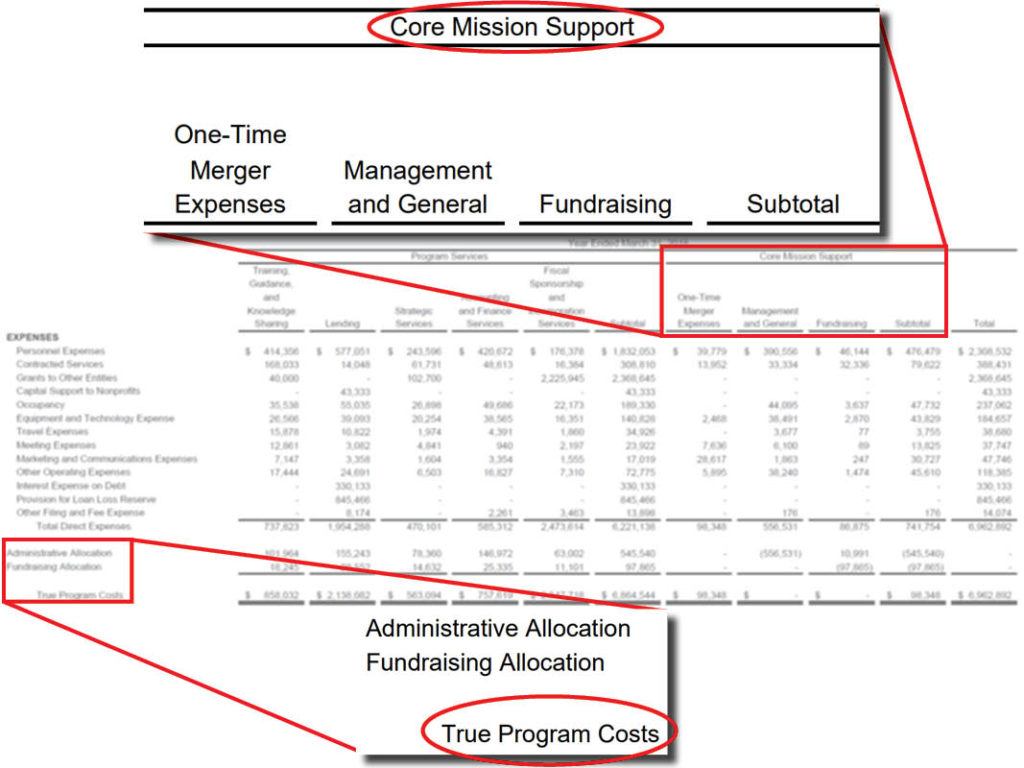

For some time now, FASB has required that nonprofits break out their expenses by three functional categories: program services, administration, and fundraising. Dividing nonprofit expenses into these three areas has led to an overemphasis on comparing the ratio of these expenses to the total. This misguided focus on functional expenses and the false correlation of this ratio to a nonprofit’s efficiency or effectiveness is called the Overhead Myth. Propel Nonprofits is a tireless advocate of the concept of Core Mission Support as a counter to the Overhead Myth, and our audit was one more place to make our case.

In what seems like a step backward, the new FASB standards require even more line item detail when reporting functional expenses. In accounting terms, this is called reporting by nature. While displaying the more detailed breakout of functional expenses is necessary to comply with FASB, using alternative terminology is a powerful way to offer a different point of view. Here are examples of terminology that Propel included in our audited financials that boldly (yes, I said boldly) goes beyond the standard template shown in examples provided by FASB. (Propel Audit, Page 6)

Along with the alternative terminology, we also reworked the usual display of functional expenses to include allocations of administrative and fundraising expenses to get to True Program Costs. Though FASB examples do not include these allocations, there is no prohibition from doing so. The table presented in this example satisfies FASB’s minimum threshold for displaying expenses by function and nature. The extra information is storytelling in action – storytelling with a purpose.

Liquidity and Availability

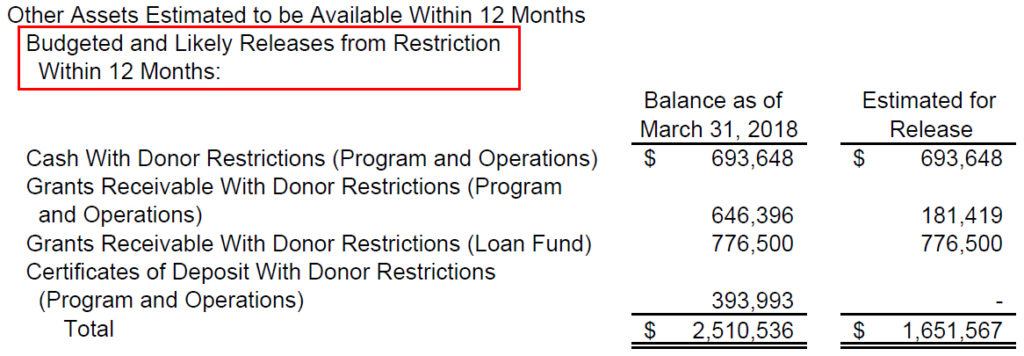

FASB’s new standards require that nonprofits include information about the liquidity and availability of funds. This information is used by donors, investors, and other stakeholders to assess the ability of a nonprofit to meet its financial needs and sustain its operations. The new standards use the typical (and arbitrary) 12-month accounting period to define what funds are available for use. But many nonprofits have business models that include revenue cycles with a variety of timeframes.

To provide a full picture of liquidity and availability, FASB requires nonprofits to provide both quantitative information (often a table) and qualitative information (often a narrative note disclosure). To tell more of our nonprofit financial story, Propel Nonprofits added a narrative description of our Operating Reserve policy and how we calculate it. This measure is not tied to the usual 12-month accounting period. Instead, our board set a policy of having 90 days of operating reserve as a benchmark, with a prescribed way of calculating the amount of reserve needed. Our note disclosure presents both the quantitative and qualitative side of our policy. (Propel Audit, Page 19) This gives statement readers insight into how our board monitors liquidity. It also showcases the board’s engagement and sophistication where it concerns financial management. There is no shame in reinforcing the view that nonprofit leadership can be financially and strategically advanced.

When defining what funds it considers available, FASB also only includes funds without donor restriction, even though nearly all nonprofits expect to use some portion of their restricted funds to carry out their daily program operations. In an even more provocative addition to the liquidity disclosure, Propel Nonprofits added a section showing the amount of restricted funding that is estimated to be released from restriction during the coming year. FASB does not include net assets with donor restrictions among those assets available for use. However, it would be a very rare circumstance in which a nonprofit would use none of its restricted funds for operations within a 12-month period. After satisfying the minimum disclosure of liquidity by first listing only those funds and assets available without donor restriction, it is perfectly acceptable to list an estimate of funds with restrictions that your nonprofit expects to release. (Propel Audit, Page 20)

Owning Your Narrative and Your Numbers

Out of fear of noncompliance, many nonprofits have too often deferred to auditors when writing the required disclosures and choosing how to display their numbers. Instead, nonprofits may boldly use their audits to showcase their mission and financial story. Using the lens of finance, we strive to focus the attention of those reading our audits on how we strategically shepherd our resources toward programmatic goals. Propel Nonprofits hopes to inspire you to shape your own financial story in an audacious audit of your own. So go ahead, exercise a bit of financial moxie. Jump through the hoops bravely. Then please share it with us when you do.

A special thank you: We’re fortunate to have great auditors, CliftonLarsonAllen, who we work with very closely throughout our audit process. You can see our full, collaborative FY2018 audit here.