Transforming Nonprofit Business Models

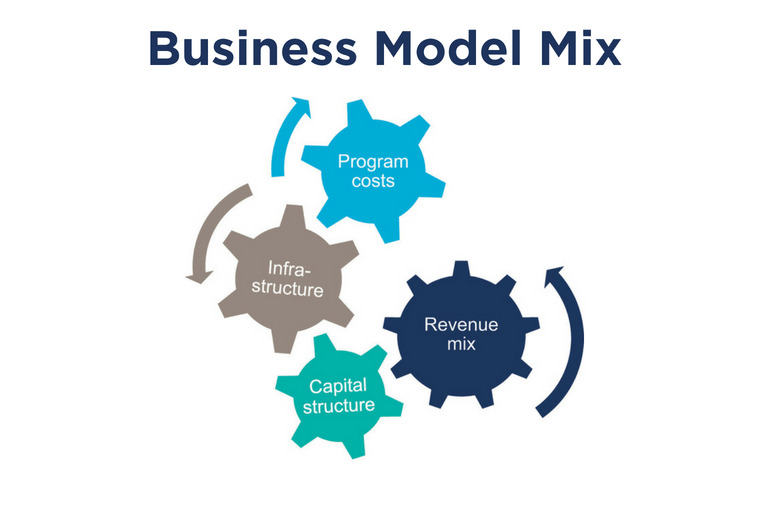

This resource explains financial structure of nonprofits, broken down into four core components. These components – revenue mix, infrastructure and expenses, program cost, and capital structure – define the business model that creates value for the community and sustains the business entity.

Nonprofits are appropriately viewed primarily as mission-driven organizations. Evaluations of success focus on an organization’s impact in the community, such as job placements, academic achievement, and family stability. However, nonprofits are business enterprises as well, built on an underlying business model that makes the programs and organizations operate and succeed. The recent economic downturn stressed many nonprofits and led to questions about the sustainability of prevailing nonprofit models. Leaders of every nonprofit must carefully assess the effectiveness of their particular structure and prepare for a potentially different approach in the future.

Business models at nonprofit organizations have never been static. The structure and composition of revenues, expenses, and capital evolves over life stages and in response to external events and internal strategy. Rather than worry if “the model is broken,” nonprofit leaders must prepare for their next business model and invest resources to sustain the mission and serve the community. This preparation consists of four steps:

- Understand the current operating model;

- Diagnose any critical weaknesses;

- Forecast and plan a structure that will address the weaknesses and be effective in the short and midterm future;

- Implement the needed, and possibly difficult, changes.

Seeking an ideal or permanent answer is not productive, nor is it likely to be successful. Organizations grow, change, contract, and change again. This is not a simple process, and it will require the commitment of staff and board leadership and a shared vision of the ultimate, mission-driven goal.

Business Model Concepts

The financial structure of nonprofits contains four core components shown in the graphic to the right. Together these define the business model that creates value for the community and sustains the business entity. The four components are closely inter-related and each will be impacted by weaknesses or changes in any of the other three. Like a set of gears, if you move one, the others shift as well. The first step – understanding the current operating model – begins with inquiries and analysis of these elements. Diagnosing the critical weaknesses requires a realistic assessment of both external economic factors and past decisions and leadership actions. Forecasting and planning may lead to significant changes that affect core organizational operations and programs.

Transforming Nonprofit Business Models

Assess the current condition of the four financial components of the business model to complete the process of developing a forecast and plan to implement the changes needed for the next stage.

Revenue Mix

The value of revenue diversification is a time-honored assumption in nonprofit financial planning. Realize though, that each different type of revenue requires a nonprofit to operate a new business. Government contracts, individual donors, and foundation grants require different infrastructure, expertise, and relationships. Most nonprofits have one or two dominant sources of revenue supplemented by one or two secondary sources. Few nonprofits can manage six or seven different revenue businesses effectively. Revenue growth is accomplished by developing reliable systems and relationships geared to those sources. The lure of diversification is understandable when you consider how difficult it is to replace a dominant revenue source. Many social service nonprofits are in this situation after having grown revenue with public funding, the very source that has been impacted most severely in the past few years.

- What is your dominant revenue source?

- How is the availability or stability of that source changing?

- Do you have other significant or secondary types of revenue that can be developed further with existing systems and capacity?

- If you need to create a new revenue type, do you have capital or capacity to invest in order to build the new business?

Infrastructure

For the last few years, nonprofits have been cutting corners and reducing costs. Many of the cuts have been in administrative expenses in order to preserve program services. Stable, effective leadership, governance, management, and fundraising are essential for longterm health. Now that all the corners have been cut, and more, nonprofits need to take a hard look at how they have operated in the past and look for ways to change the expense structure while maintaining vital infrastructure. Overall, nonprofit budgets are often developed by starting with the previous budget and adding or subtracting based on available resources. This process reinforces “we’ve always done it that way” thinking. A sustainable business model needs new thinking. Since personnel usually accounts for more than 60% of expenses, the review often includes changes to staff roles and responsibilities. The “answer” isn’t necessarily to reduce staff or salaries, but may result in new or different positions. Every expense area needs thorough review to seek different ways of accomplishing the nonprofit’s goals.

- What are the three largest expense types?

- Do you have a way to evaluate the effectiveness of these three costs in carrying out strategies?

- What are the possible alternative structures or options to deliver similar results?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the current infrastructure?

- What could be accomplished with stronger systems and support?

Cost of Effective Programs

Understanding the true cost of delivering their programs enables nonprofits to make clear decisions and choices about the value and priority of a portfolio of services. The true cost of programs includes direct costs that are normally attributed to the program, plus allocations for common costs such as occupancy, technology, office expenses, and communications. Programs also require the services of human resources, accounting, and other centralized administrative functions. These costs should be shared by programs using a rational and consistent method. The true costs of programs may be very different from the costs stated in contracts, and is often much higher than the prices paid by third parties or funders. The difference between cost and price is subsidized by the organization using contributions, general operating funds, earned income, or reserves. Allocating the available subsidy is one of a nonprofit’s most important financial decisions and should be made intentionally based on mission, impact, and strategy.

- Do you know the true program cost of core programs?

- Does this translate to a “per unit” cost?

- For programs that require subsidy, is the decision to provide subsidy justified by mission fit and program effectiveness?

- Does the organization have sufficient subsidy dollars available? If not, will reductions or changes be based on mission and program effectiveness?

Capital Structure

Without access to an equity source, capital at nonprofits is accumulated incrementally through fundraising, capital campaigns for buildings and endowments, and budget surpluses in the good years. The capital structure is revealed in the asset composition. Many nonprofits have substantial assets but virtually no liquidity because their assets are invested in buildings, long-term endowments, or restricted cash. Capital has been underemphasized in the nonprofit sector for years, with little attention paid to balance sheets and net assets. The importance of appropriate capital structure has never been clearer than now because unrestricted working capital creates capacity to invest in changes such as new fundraising initiatives, program development, and branding and marketing. Capital is also represented in the nonprofit’s financial obligations such as mortgages, long-term bonds, and other liabilities. The structure and cash requirements of these obligations can have a big impact on financial flexibility and cash flow.

- What are the two largest assets? Are they liquid or illiquid, restricted or unrestricted?

- Do the two or three largest assets significantly contribute to mission and program strategy?

- What are the two largest liabilities?

- Does the structure of these liabilities still fit the organization’s operations and budget?

- How much does the organization have in unrestricted net assets? What is readily available in cash and liquid funds to invest in the organization’s future strategies?

Copyright © 2024 Propel Nonprofits